Written records exist for almost 200 years of the use of Oȟéyawahe, “the place much visited” or Pilot Knob, for burials by Native Americans and subsequently by European Americans. Chris Leith, Dakota spiritual leader at Prairie Island, says that Pilot Knob is considered to be a “sacred landmark,” associated with the powerful figure of Dakota belief, Unktehi, used in the health-giving Wakan Ceremony, and as a place for burials. Leith states that burials were placed there because “people knew that the place is sacred and nobody will disturb it.”

Dakota burials were often placed on high promontories. Native Americans marked burials with wooden markers or stones in ways that either were seen as inadequate by whites or were entirely imperceptible to them. According to the missionary Samuel Pond, when a person died he or she was dressed in his or her best clothes and wrapped in a blanket to be placed on a burial scaffold or in the branches of a tree. After remaining there for days or even months during the winter, the bodies were buried in the ground in graves two to three feet deep. Graves were “protected by picket fences or by setting a row of posts on each side of the grave, leaning against each other at the top of the grave, the ends of the grave being protected by uprights posts.” The wood markers deteriorated over time.

Whites who were unfamiliar with these practices were sometimes shocked or surprised. Charles Lanman, an artist who visited the hill in 1846, did not see the graves there and described it only as a “grass-covered peak commanding a most magnificent series of views.” Lanman had seen Seth Eastman’s pictures of Dakota graves and remarked that it was “singular and affecting.” Describing the bark-covered grave houses typical of Ojibwe burials, Lanman wrote: “What a strange contrast in every particular did it present to the grave-yards of the civilized world! Not one of all this multitude had died in peace, or with a knowledge of the true God. Here were no sculptured monuments, no names, no epitaphs;—nothing but solitude and utter desolation.”

This statement was typical of many European-American descriptions of Native American burial practices. As Michael Scott asks: “The European way, they put their people in a coffin and 4″ thick concrete and bury them, and would never think of moving them. The Europeans put a head stone to mark the grave and nobody in their right mind would ever think or even suggest moving them! Are they any different?”

European-Americans also noted the lack of written documents recording the names of Native American burials. Both the St. Peters Church Cemetery, established on the north end of Pilot Knob in the 1840s, and the Acacia Park Cemetery, started on the center part of the hill in 1928, had written cemetery registers. However, as Father Kevin Clinton, pastor of St. Peter’s Catholic Church, states: “The Native Americans of this area regard the Pilot Knob site as a sacred area used by their ancestors long before things were written down. Their ‘registry of burials’ is recorded in their oral tradition.”

Acacia Park Cemetery has made no comparable acknowledgement of the consecration of Oheyawahi/ Pilot Knob by Dakota people. When Acacia Cemetery was established, its leaders made no mention of the previous use of the area by the Dakota for burials, although landscaping had revealed bones of Native Americans, as reported by newspapers and magazines over the years.

The documents quoted below record some of what has been written about burials on Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob over the last 200 years. Even though some of it was written by culturally insensitive Europeans and European-Americans, this information is important in documenting the use of this area as a burial place. It is hoped that more Dakota people will add their knowledge to this register so that the importance of this place as a cemetery can be more widely known and so that the place can be adequately protected.

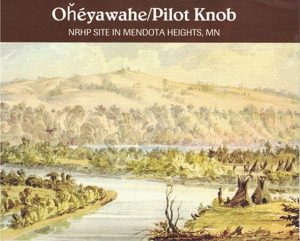

Seth Eastman, Pilots Knob. Mouth of the St. Peters River. A watercolor showing Pilot Knob from below Fort Snelling looking southeast. A burial scaffold is visible at the summit. Minnesota Historical Society.

Seth Eastman, Distant View of Fort Snelling, from the area of Camp Coldwater. Pilot Knob with a burial scaffold on its summit is visible in the background at right. Minnesota Historical Society.

Seth Eastman, Medicine Dance of the Sioux or Dakota Indians on the St. Peters River near Fort Snelling. A watercolor showing the Wakan ceremony, possibly on Pilot Knob where it was sometimes practiced. Minnesota Historical Society.

p. 2: “Opposite Fort Snelling is Pilot Knob, a high peak, used as a burial-place by the Indians; just below it is the village of Mendota, or the ‘Meeting of the Waters.’”

p. 71: “The sky was without a cloud when the sun rose on the Mississippi. The morning mists passed slowly away as if they loved to linger round the hills. Pilot Knob rose above them, proud to be the burial place of her warrior children.”

p. 113. “From the summit we were favored with a delightful view of the surrounding country. . . . There were indications that this mound had formerly been held sacred by the Indians, as the burial place of their dead.”

“Narrative of Eagle-Eye and Scarlet-Dove.

“Eagle Eye was the name of a Dakota who lived more than a century ago. He was the only son of a noted war Prophet. At the early age of twenty, he had distinguished himself on the field of blood and carnage, and was admitted to a conspicuous place in the ceremony around the painted board, where the Dakota warrior is permitted boastfully to narrate his military exploits. On these occasions, four quills of the War Eagle, crested his proud brow, while in the midst of the wild war yell of a hundred savage voices he related in the hearing of astonished spectators the exciting circumstances of those daring acts by which he won them.

“When wending the war path, Eagle-Eye carried a heart of stone that could meet any danger, or death. . . . Success in war though it gratified his savage nature did not render it happy; but he ever felt an anxious longing—a painful emptiness which at times beclouded all his joys. At length, the strong, struggling affections of his lonely heart, fixed upon the orphan daughter of a distinguished Mdewakantonwan brave, whose name was Scarlet-Dove. She was young and fair, and reciprocated his love; and they were joined in wedlock according to the most honorable custom of the Dakotas. Scarlet-Dove filled the void of Eagle-Eye’s soul, and she coveted no other dwelling place. . . .

“A few short moons after the celebration of their nuptials Eagle-Eye and Scarlet-Dove, with their people, dropped down the Mississippi to Lake Pepin, in their canoes, and then proceeded by land to their hunting grounds east of the river.

“It chanced one day, as Eagle-Eye was stealing to an unsuspecting deer, under cover of the thick foliage of the under-brush an arrow pierced his heart. He only pronounced the name ‘Scarlet Dove,’ and expired. The cruel arrow had been driven by the twanging bow-string of the comrade of Eagle-Eye, who, unconscious of the presence of his friend, had approached from the opposite direction.

“We shall leave to the gentle reader to imagine what were the emotions of Scarlet-Dove when the sad tidings reached her. We may not attempt to speak such grief as her’s was; her own acts best express those big emotions, which well nigh burst her tender bosom.—After a few days nights of fruitless wailing and self-torture, despair settled down upon her and drove her murderous talons deep into her wounded heart; and in silent agony, which only the youthful widow can appreciate, she nicely wrapped the cold remains of Eagle-Eye in the ornamented skins of animals which he had brought back from the chase, and placing them upon a temporary scaffold, erected for the purpose, sat down under them. She still followed the moving party, carrying on her back the dead body of Eagle-Eye—all that was dear to her this side of the spirit-land.

“At every encampment she laid the body up in the manner already mentioned, and set down to watch it and mourn. When she had reached the Minnesota river, a distance of more then a hundred miles, Scarlet-Dove brought forks and poles from the woods and erected a permanent scaffold, on that beautiful hill opposite the site of Fort Snelling in the rear of the little town of Mendota, which is known by the name of Pilot Knob. Having adjusted the remains of the unfortunate object of her love upon this elevation, with the strap by which she had carried her precious burden, Scarlet-Dove hung herself to the scaffold and died. Her highest hope was to meet the beloved spirit of her Eagle-Eye in the world of spirits.”

p. 114: “On the death of an Indian his body is wrapped in his robe or blanket, & since their intercourse with the whites a coffin is, if possible, procured. It is then placed upon a scaffold, raised six or seven feet from the ground, where it remains for several months, & even years, often until it falls to pieces & the bones are scattered upon the ground, to be collected & deposited in a grave. The coffins are often bound around with a red or brilliant colored piece of cloth, which makes them conspicuous at a distance. Frequently portions of choice food are placed at a grave for the use of the deceased, who consumes the spiritual portion, when the young men eat the remainder. A watch is concealed near-by who sees that no animal disturbs the repast & when a sufficient length of time has elapsed for the consumption of the spiritual portion, she leaves it. If placed hot, it looses the spiritual portion with its [heat].”

p. 241: “The view from Pilot Knob, once a favourite burial place of the Sioux, is very extensive, commanding the valley of the St. Peters, the Mississippi Fort Snelling, St. Paul and St. Anthony.”

Frank B. Mayer, Valley of the St. Peter’s or Minnesota river, from Pilot Knob..Mendota. A pencil sketch, original in the Newberry Library, Chicago, looking southwest from the summit, showing at right in the picture, the edge of a burial scaffold.

“The military reservation embraces an area of about ten square miles around Fort Snelling. Over almost this entire extent the eye may wander from one of the bastions of the fort; and from Pilot Knob (a supposed sacred sepulchral mound of the ancient people), in the rear of Mendota, opposite the fortress, a magnificent view is obtained.”

“Ascended a hill just below this village this afternoon from which I had a full view of Saint Paul . . . Saint Anthony . . . the Fort. . . . This hill should be the site of an observatory. How magnificently grand must be the view from this point in the blooming Spring the verdant Summer or golden Autumn. And as if to add a melancholy interest to this enchanted spot, upon the very summit is an ancient as well as modern burying ground where the natives have perhaps for centuries deposited their dead.”

“The highest point of land near Mendota is ‘Pilot Knob,’ which affords a fine view of St. Paul and St. Anthony. . . . During the present season this is completely carpeted with golden rod, aster, bergamot, and wild flowers of almost every size and hue. . . . Pilot Knob was once an Indian burying ground, and as we bent to look into the holes which the gopher has burrowed into the rich soil, we saw the skull doubtless of some Sioux warrior which had laid in its pleasant resting place for many years.”

“The Indian Prisoners.

The inclosure which answers for the ‘prison’ of the captive Indians, has been moved from the bottom land near the mouth of the Minnesota river, and is now located on the edge of the table land about a mile from the Fort, towards Bloomington. . . . Into this little ‘city’ are crowded 1,600 souls; and of course, filth and degradation are on every hand. . . . A number of paposes have died during the winter of infantile diseases, and were usually buried in an old Indian burial ground back of Mendota.”

“The Pilot Knob is an ancient burial place of the Dakota’s, and is yearly visited by many of the Indians of that nation.”

“From Pilot Knob can be witnessed one unending panorama of natural beauty from all points of the compass, which impresses the eye more as a picture than the grand handiwork of a great unseen Power. This high point of ground was at one time the burial place of many bodies of defunct Sioux Indians, lofty places, when accessible, being always chosen for that purpose.”

“Pilot Knob is the spot where the Treaty of Mendota was signed with the Indians in 1851 which opened land west of the Minnesota River to settlers. It was used as a burying ground for years by the Indians and we would find arrows and bones digging up on the hill when we were boys.”

“Once Indian Cemetery.

“Negotiations for the purchase of the Pilot Knob for cemetery purposes have been under way for the past six weeks. Its final purchase reverts the historic landmark to one of its original uses. Prior to General Sibley’s arrival at Pilot Knob in November 1834, the Knob was used as a burial ground for Sioux Indian tribes of the vicinity. Its original name, so far as records of the Minnesota State Historical society reveal was ‘La Butte des Morts,’ which translated reads ‘The Knoll of the Dead.’”

“Originally, the plot was used as a burial ground for the neighboring Sioux Indian tribes, and its development by the Masonic group will revert it to its original uses. According to records of the Minnesota State Historical society, Pilot Knob was originally known as ‘La Butte des Morts’ which translates “The Knoll of the Dead.”

“The historical value of Pilot Knob extends far back into early history of the Northwest according to the records of the Minnesota State Historical society. The site was used by Indians for their solemn pow-wows between tribes and the leading braves of the warrring tribes were buried on the summit of the knob. During the landscaping of the grounds many graves of the Indians were found and the bones carefully transferred to other parts of the park and there reburied. . . . Valuing the historicity of the grounds the committee has pledged itself to erect memorials to the men Indian and white, who have made Pilot Knob famous.”

p. 5. Judge Horace D. Dickinson, Master of Ceremonies: “First of all it has occurred to me since I was introduced here this afternoon that on this historical spot, known as Pilot Knob, way back in 1851 there was signed a treaty with the Government whereby all this property was ceded to the United States and all claims of the Indians thereby relinquished, and one of the Indian Chiefs of many Chiefs who signed that cession was Wacouta—Chief of the Red Wing band—I take pleasure in introducing to you at this moment his grand-daughter, Mrs. Mary Louis Bluestone.

“This is a Consecration, I have been informed, rather than strictly speaking a Dedication —a Consecration of this beautiful burial ground known as the Minnesota-Acacia Park Cemetery. I think you will agree with me that it is unrivaled in its situation for beauty, loveliness and promise of development in the future, overlooking as it does the great Father of Waters at its junction or confluence with its tributary—the Minnesota. It is destined to be to the Northwest what that beautiful Arlington on the Potomac is to the nation—dedicated exclusively to members of the Masonic fraternity, their families, and members of the Eastern Star. It will soon occupy in our affections a place of great devotion—shrine to friendship, love and memory.”

p. 7. Rev. A. G. Pinkham [whose wife was the first person buried in the cemetery]: “Whereas the Minnesota-Acacia Park Cemetery Association has set apart this plot of ground as a place for the burial of their dead, and have requested us to consecrate the same under the name of Minnesota-Acacia Park Cemetery, and forever set it apart from all unworthy or common uses—

“We do declare this cemetery so consecrated and forever set apart from all profane and common uses, and dedicated to the burial of Masons, and their families. . . .

“The blessing of God Almighty, the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, be ever upon this place, and sanctify and keep it holy, that it may be a fit resting place for the bodies of His saints, until the day of Lord Jesus, when He shall come to judge the quick and the dead.”

p. 10-11. Frederick E. Jenkins, Worthy Grand Patron, Order Eastern Star: “The Founders of this Cemetery are to be congratulated on their choice of a site. it is both beautiful and commanding, and when all the plans are worked out and nature has had time to do her part it will be a wonderfully beautiful place and as time goes on and on it will be consecrated and reconsecrated as the beautiful ritual of Church, Chapter or Lodge is used in laying away our loved ones.”

“Arising from the top of a high bluff on the west bank of the Missouri river in Nebraska is a mound of regular form and considerable dimension. The custom was in times of the past that when a famous Indian Chief died he was fastened in an erect position astride his horse and the horse was lead to the top of a prominence and caused to face the East. Earth was piled little by little until both horse and rider were completely buried. This was done in the expectation that both horse and rider would some day live in the happy hunting ground, the heaven of the aborigines. . . . My friends, it requires but little stretch of the imagination to think that [the] wish . . . of the Indian Chief and the wish of all true believers, in fact, the wish of all of us, may be fulfilled, the wish that some day out of the dawn will come a glorious resurrection. May this be the cherished hope of all those whose loved ones are laid to rest in this consecrated ground.”

p. 13. Governor Theodore Christianson [of Minnesota]: “Today we are assembled to dedicate a cemetery. We have met to set aside a piece of ground to be used as a last resting place for Masons and members of their families. . . . But we are dedicating this place, not only as a ‘city of the dead,’ but as a rendezvous of the living, where men and women shall ever and anon gather to renew memories, to make new resolves, and to give themselves to higher loyalties.”

“Long before the advent of the white man, we know from Indian legend and customs that Pilot Knob served as a watch tower. Its commanding position is proof enough of that. From its summit, it is not hard to visualize, even today, how keen-eyed braves watched the approaches from the north for war parties, and sent up flares to warn tribesmen whose camp fires burned up and down the shore-line far below. Pilot Knob’s lofty height, however, made it more than a look-out. Here on the high plateau, Indians, who share with all mankind the aspiration to reach up to the heavens, buried their dead under the blue skies of Pilot Knob. Bones and relics recovered on the ground some years ago have been reverently set aside to be buried at some future date with fitting ceremonials.”

“Impressive ceremonies of dedication will take place Sunday, Sept. 30, at Acacia cemetery, Mendota, when a $35,000 monument will be unveiled high on Pilot Knob. . . . Pilot Knob is the sacred burial grounds of countless tribes of Indians.”

July 1, 1962: “Received a call from [blank]. He reported that a shed on No. end of Cemetery had been broken into and a vault with Indian bones had been open. He stated that there were seven skulls in the vault, six were missing, also some one had broken into the basement of the house where he keeps equipment, this happened between Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning. . . . [Blank] had one skull in his car, and a case of Grain Belt, three-two beer was found in the grass along side of the car.”

[Report from unnamed person]. “About 5:30 today I was at the Spur Station in South St. Paul when two kids I know came to the station and were telling us that their [there?] was a place that had skeleton bones in a coffin and asked us if wanted to see it then so [we] went in their car and me and [blank] went in his car and when we got to the place we walk over to this old garage & climb in threw the window & were looking for two jaw bones & me & [blank] were watching them & after they couldn’t find them we left & when we go outside there was a car pulling into the yard and started to yell & than we left.”

[Report from unnamed person employed at Doddway Frame & Align]. “I know this person named he told me about a bunch of bones in a casket. He did not know where they came from and was curious. He told me that some friend of his found them by accident. I didn’t believe him at first. He said that he could show them to me. & I went there and found a casket full of bones in a deserted shack. We went uptown to see a friend. We told him about the bones and two other friends heard us. They told us to take them there, so we did. That’s when Deputy Sheriff and Mr. Baldwin came and picked me up. [Blank] and I were there before we went to S. St. Paul. He showed me the bones and we took one skull out of curiosity.”

[Report from an unnamed person]. “Meet these t[w]o guys at a gas station on Concord Street. They told me that they know where there was a bunch of bones so we went out there to see them. and went inside[.] I stand out side. They came back out and we saw these car[s] so started running. These man was waiting at the car he told us we were grave robbing[.] me and [blank] [left].”

[Report from an unnamed person]. “On Sat. June 30th, [blank] and I, [and] another fellow went to a shed in the Cemetary—after [blank] told us about a box of bones, we went in through a broken window and took the cover off a casket. We found a bunch of bones and several skulls. We left and did not take anything. On Sunday afternoon I met [blank] in So. St. Paul and I told him about the bones. Also with us at this time there were two other fellows. I only knew one. . . . We had a case of beer that had been purchased in St. Paul and decided to go to the Cemetary. I and went in through the window. We lifted the top off and I showed him the bones. and the driver of the 57 Olds stood outside. They hollared that someone was coming and we ran outside. I was picked up by Deputy Sheriff LeClair on Lexington Avenue.”

[Written Statement from student at Cretin High School]. “I was with [blank] and [blank] last Saturday night at Acacia Cemetery. We climb through the window. I stood inside while the others opened the vault. [Blank] took out one skull. We went out the window and went over to the brick house. Then brake the lock on the door. Then went in the brick house with [blank]. Then [blank] and [blank] went home, and so did I. This was about 6:30.”

“Mendota Heights. Twenty juveniles were arrested this week for breaking into a shed in Acacia Park Cemetery and stealing seven Indian skulls out of a burial vault. Vandalism and beer drinking were also reported by the local police.

“Chief of Police Martin Baldwin, for five weeks in his new office in Mendota Heights, said two youths at the age of 19 were turned over to locals Justice of Peace Thomas R. Bernier for subsequent trial.

“The 20 culprits, who seemed to have returned to the scene of much vandalism, breaking windows in shed and an old house, desecrating graves and swimming in drinking water [in the cemetery’s reservoir], were from Mendota Heights, Mendota, Minneapolis, and West St. Paul.

“Three of the skulls have been recovered so far. Byron Lyons, general manager of Acacia Park cemetery, a self-sustaining and non-profit association, said the skulls had been stolen from a burial vault which also contains two baby skulls and a number of bones recovered from the old Indian burial plot, the Pilot Knob.

“The sacredness of the Indian burial plot had been taken into consideration, as the board of associates have planned to bury the remains of the Indians when a mausoleum will be erected in the future, Lyons said.

“The three skulls were returned to the cemetery and placed in a safe place, Lyons added. He was disturbed by [the] vandalism and said windows had been broken about 20 times in the shed where the skulls were found.

“The thieves apparently hesitated picking up the bones and the skulls of two Indian children. It tickled the imagination of the young vandals, however, to sneak away with the sacred remains of the dead. They had no occasion to know that the skulls belonged to Indians.”

[Caption under photograph of three skulls posed in front of a picture of Indian man with blanket]: “Three skulls were recovered through the effort of Mendota Heights police department. Chief of Police Martin Baldwin experienced his second big problem since his arrival from South St. Paul almost six weeks ago. Previously, the new chief worked with the case of stolen tires. Now he is engaged in a frantic search for four missing skulls of Indians buried at the historic Pilot Knob. Acacia Park Cemetery would wish to give an honorable burial to the Indian remains.”

“On today’s date OSA [Office of State Archaeologist] received the following materials from the above: reported American Indian remains (multiple individuals, unknown number) described in 07.13.1962 ‘West St. Paul Booster’ newspaper article; note: the cemetery has no further documentation on these remains.”

“On behalf of the Board of Directors of Acacia Park Cemetery, I am responding to your letter dated Feb. 20, 2003 regarding the existence of human remains in our possession. After receiving your letter, we did discover a small concrete vault that contained human remains. As no one currently employed by the cemetery knows where these remains came from or if they are of Indian origin, we contacted the state archaeologist, in accordance with Minn. Stat. 307.08, Subd. 4. Last Thursday, March 20, 2003, the state archaeologist came to the cemetery and took possession of the human remains to determine their origin.”

“This letter details my observations and conclusions of the forensic anthropological analysis of the three boxes of human remains you transported to Madison, Wisconsin on April 8, 2003. My charge was to examine all of the bones and bone fragments to determine which, if any, could be presumptively or positively attributed to Native American ancestry. I was not asked to determine the minimum number of individuals represented. In total two manibular (jaw) fragments were presumptively identified as Native American. Twenty-two femur (thigh bone) fragments and three virtually complete skulls were positively identified as Native American based on morphological traits and measurements. . . . Given the context of discovery, it is also likely that this tibial shaft fragment is also of Native American origin.”

[In answer to a question about why there were burials on Pilot Knob/Oheyawahi]: “The reason why they did that, people knew that the place is sacred and nobody will disturb it. Like a cemetery.”

“Pilot Knob has been utilized by Native Americans for a period of greater than 10,000 years, and while it is unknown exactly how long the Dakota have been present it is referenced as a burial site by many through the post contact period up to the 1850’s. As sites for burial, these locations are sacred to us and need to be respected and left alone. OHEYAWAHE in Dakota means ‘a hill that is visited much”; not only was this area used by Native Americans long before the settlers arrived it was also a place of ceremonies between the two cultures. This site is believed to be the location of the Treaty of Mendota of 1851. . . . Given the history of development in the area and the subsequent treatment of Dakota burial sites we have serious reservations about the ability of developers to treat this area with the sensitivity that it requires.”

“August 8, 2003: Bob Brown [chairman of the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota community], age 62, died. A four day ceremony began.

“August 10, 2003: a pipe ceremony is held on Pilot Knob.

“August 12, 2003: A funeral service conducted by [Rev. Kevin Clinton] the priest of St. Peter’s and Chris Leith [Dakota religious leader from Prairie Island] is performed at St. Peter’s Church. Burial took place afterwards in Acacia Cemetery on Pilot Knob.”

“St. Peter’s Parish cemetery is a historic and valued part of our parish community. We have buried the ancestors of our faith community back to the 1850s. We carefully record in our cemetery registry the name and information of each individual buried in St. Peter’s cemetery. This coming November 2 is the Feast of All Souls when we especially honor the ‘faithful departed.’ If anything would threaten the grounds of our parish cemetery, there would be immediate and powerful efforts organized to protect this sacred and consecrated ground. The Native Americans of this area regard the Pilot Knob site as a sacred area used by their ancestors long before things were written down. Their ‘registry of burials’ is recorded in their oral tradition. I confirm the reality of the area being an ancient burial ground because St. Peter’s Cemetery is just across the road from the Pilot Knob site. On one occasion, when we dug a grave in St. Peter’s Cemetery, we came across the bones of an indigenous person 1500 years old We immediately turn over the bones for re-burial at another sacred site. Proper burial and showing respect for one’s ancestors is a big need of Native people. This need is understood and protected by the policies of the State DNR. Native peoples have lost much from the rich cultural heritage of their ancestors. The losses they have experienced over the last 150 years heightens even more the importance of respecting and honoring the Pilot Knob site. Their ancestors were here before us. They made room for us and our own ancestors to live here. Had they known what was to transpire following signing the Treaty in their ancestors’ grave yard, they would have certainly protected Pilot Knob from 1851 on. The fact is that they understood little of what they were really giving away in the 1851 transaction. If this site is developed to commemorate the Treaty of 1851 then, we honor them and their ancestors. We honor what they lost and gave so that others, so different than them, could have a new home in a new land. There is a growing appreciation for the cultural heritage of indigenous people among all Americans. The Treaty Site of 1851 teaches gratitude for those who gave so that we would have.”

“The following is the presentation I gave at the Mdote Lecture Series Monday evening, Oct. 27, 2003. [In the original presentation Scott held two boxes filled with dirt from Pilot Knob, one with a model of a headstone, marked “RIP”]:

“I want to talk to you about the sacredness and significance between the indigenous people’s burials and the European burials, because there is a difference. The European way they put their people in a coffin and 4” thick concrete and bury them, and would never think of moving them. [Showing first box.] The Europeans put a head stone to mark the grave and nobody in their right mind would ever think or even suggest moving them! Are they any different?

“In our way [showing second box], no head stone, possibly small rocks—it’s kind of a personal thing! If there are no head stones—it’s dig on. No head stones, so you don’t mean anything, that’s how our people are treated. My ancestors are in the dirt. Contractors come and don’t see head stones and they do their own thing and start digging. In our way [no coffins]. Bulldozers digging up they ground find a bone, put it aside and then more bulldozers come and find more bones and put them with the others. We’ll take the bones and rebury them over there! Now that the bones are moved it’s not sacred. You really can’t do that.

“OK, ‘so no more bones, start digging.’ By moving the bones, it does not change the significance of the land. You can’t get dust out of the dirt. Just as you can’t pull salt out of saltwater, you have to deal with it, it’s in the water. OK, now there are no more bones start the machines and start plowing. Now by taking the bones out of our graves and setting them over there and having a ceremony and take the bones and bury them over there! YOU CAN’T DO THAT! When you really think about that, what was around those bones? Where is the flesh, hair, eyelashes, hearts, intestines, by moving the bones, doesn’t change the significance of the land. This to me is a way to make yourself go to sleep at night after doing this, without any guilt. It’s impossible to get the remains out of the dirt.

“This is Pilot Knob (sifting sand through his fingers). These are my ancestors, mine and all indigenous people, these are our ancestors. Their hair and skin is in the dirt, in the whole Pilot Knob up there. St. Peter’s cemetery, they cut a big V out to make Hwy. 110. What’s on the back side of 110, Pilot Knob—other side of 110 is European cemetery. This is St. Peter’s cemetery. My Great Grandmother and Grandfather are buried in St. Peter’s Cemetery, but it’s the whole hill, not just a corner here or down by Hwy. 13—it’s the whole hill. My ancestors are in the whole hill, in the dirt, you can not remove them. It’s impossible to remove them!!!

“The State Archaeologist Mark Dudzik –‘We found your bones and moved them. They are over there—everything is cool!’ If they can scientifically prove to me they can get my ancestors’ ashes out of the dirt, then I will never say another word, but it’s physically impossible. Now the European people here have their head stones. [Moves head stone that has RIP on it from European grave to Indian grave.] Would this have saved my people?? Probably not!! People should always have RIP—it can’t be any simpler than that, but since this head stone is on the European grave and not on the Indian grave, moving it to the Indian grave means nothing. Is it the head stone that is their key? I don’t know. I can’t thing like they do, because it goofs up my mind. I don’t want to, I want to think positive.

“So I would say, for what I know right now, it’s the head stone that gives a burial RIP, and sometimes they put up fences. We maybe put a rock around it or that stuff. Some burials have rocks all around it, but never a head stone in our traditions, but I’m talking about way far back, before the Europeans came here with their caskets. These are my relatives here, and you can’t just move my relatives. If you’re in a coffin and they dig you up and take your bones out of the coffin, the ashes are in the coffins, not in the dirt!!!

“I feel bad that my Uncle Bob had to be buried in a coffin, so he won’t be in the dirt. You can’t tell the Europeans that they are in the dirt, because they are NOT!! We put our people on scaffolds until they are bones. The remains fell to the ground! To remove the bones doesn’t change the dirt. All our indigenous people are in the dirt!! They think by moving the bones the earth is OK to develop. NO! NO! It’s a cop-out; you are lying to yourself so you can go to sleep at night, without any guilt. If they can prove to me they can take our dust out of that dirt, I’ll never say another word about it.”

“I am a Mdewakanton Dakota, born and raised on the Lower Sioux Reservation in Morton, Minnesota. My parents and grandparents through oral spiritual and cultural tradition taught us that our origin began at the mouth of the lower Minnesota River. Our spiritual leaders followed the instructions given to them through ceremony from Wakan Tonka, the great mystery. Through these ceremonies, the ground work of our culture was laid, our customs, language, songs, the drum, all the teachings of how to walk and live life were there to follow. When it was our turn to go to the spirit world, those teachings also had instructions. The Dakota people were brought back to the sacred area of their origin (the mouth of the Minnesota River). There they were given the proper ceremony to help them get back to the spirit world. Their body and personal belongings were put back to our Mother Earth to rest in peace. My great great great grandfather Little Crow signed the first treaty with the U. S. Government in 1805—‘Pikes Treaty.’ I can also trace my ancestry back to the 16 and 17 hundreds. One of my Great Great Grandfathers, John Bluestone buried his grandson on Pilot Knob hill. He would be my second great cousin in white man’s terminology.”

“In the Dakota language, the word OHEYAWAHIis also used to describe ceremonial ground used to practice many sacred Lifeways: wocekiya, hanbdeceya, oinikaga, hunka kagapi wiconhanpi. Respectively, these Lifeways are of prayer, crying for a vision, purification, making relatives. . . . The burial of the Dakota in this area is not in question. All of the evidence concludes that the land underlying the proposed development site is a cemetery, even as defined under state law. Even when a body has decomposed, been moved, otherwise altered or entirely removed, the sanctity of the site as a cemetery remains. . . . The stark differences between native burial grounds and a modern cemetery must be taken into account. Our ancestors were not buried in caskets, nor marked by a tombstone. The fact that our ancestors have not been buried there for over 150 years means that human remains have decomposed to an extraordinary degree. Despite decomposition and despite previous disturbances, the site is most likely a burial ground/ cemetery. By comparison to the notion of a cemetery to which the City Council is likely familiar with, should a tombstone be removed or destroyed or a portion of a cemetery damaged, the site is still a cemetery/burial ground.”